Julia Margaret Cameron, Margaret Bourke-White e il loro contributo alla Storia della Fotografia

L’invenzione della fotografia segnò un’epoca: era l’inizio dell’Ottocento e la riproduzione di immagini fino a quel momento era una prerogativa della pittura.

La nuova tecnica sconvolse e divise l’opinione pubblica: c’era chi sosteneva che avrebbe sostituito il disegno, chi la temeva considerandola addirittura immorale e chi invece salutava il nuovo mezzo come la più grande invenzione del secolo.

Certo, la fotografia degli albori era molto diversa da come la conosciamo oggi: i dagherrotipi richiedevano tempi di posa lunghissimi ed erano pesanti lastre di rame argentato sulle quali l’immagine appariva come un’ombra; venivano chiamati anche “specchi della memoria” ed erano pezzi unici, non riproducibili.

In molti si dedicarono alla sperimentazione e alla ricerca, e nel giro di alcuni decenni la tecnica venne notevolmente migliorata: si lavorò per ottenere maggiore fotosensibilità al fine di ridurre i tempi, per produrre più copie con una buona definizione e per stampare su carta. Lo sviluppo della tecnica ampliò le possibilità del mezzo e, dopo la metà del secolo, i fotografi iniziarono a esplorare nuove possibilità creative.

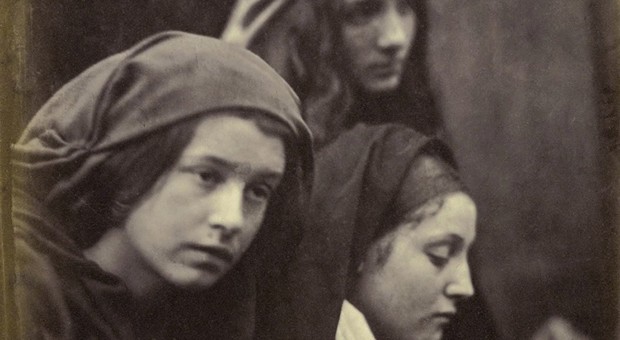

Quando Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) ricevette in dono dalla figlia il suo primo apparecchio fotografico era il 1863; i familiari speravano che la donna, che stava attraversando un periodo difficile, avrebbe trovato nella fotografia nuovi stimoli e interessi, e così accadde: presto la Cameron esplorò le differenti opportunità che il mezzo poteva offrire e, proprio perché approcciò la tecnica da dilettante, si smarcò dai canoni rappresentativi dell’epoca ed elaborò uno stile personale. I suoi ritratti erano volutamente sfocati, mossi, annebbiati, e proprio questa vaghezza li caricava di fascino e suggestione; queste immagini sollecitarono grande interesse, in particolare tra i pittori preraffaelliti, e per la prima volta si sentì parlare di “arte fotografica”.

La Cameron aveva così raggiunto il suo proposito: in un diario del periodo aveva scritto: «La mia prima aspirazione è nobilitare la fotografia e assicurarle il carattere e l’uso di una grande Arte». Nel 1865 espose pubblicamente una serie di fotografie a Londra, al South Kensington Museum (oggi è il Victoria & Albert Museum) e ottenne di poter utilizzare alcuni ambienti del museo come studio fotografico, anticipando così la pratica della “residenza d’artista”.

Margaret Bourke-White, la prima reporter di guerra

Le ricerche per migliorare la tecnica fotografica continuarono incessantemente orientandosi verso due obiettivi principali: contrarre al minimo i tempi di posa, per poter scattare istantanee, e ridurre le dimensioni dell’apparecchio, rendendolo portatile.

Nel 1925 la Leitz mise in commercio un prodotto altamente innovativo: si trattava di Leica, una macchina minuscola con pellicola 35 mm. Questo apparecchio ebbe una fortuna eccezionale e divenne simbolo del moderno fotogiornalismo, che proprio in quel periodo si stava affermando.

I giornali iniziavano infatti a pubblicare quotidianamente fotografie senza che ciò gravasse in modo eccessivo sui costi editoriali; negli anni Trenta si progettarono pubblicazioni esclusivamente pensate per le riproduzioni fotografiche: la rivista “Life”, fondata negli Stati Uniti nel 1936, fu la più celebre.

La prima copertina di questa pubblicazione segnò una svolta nel mondo della fotografia al femminile, fu infatti assegnata ad una donna: Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971). Fu l’inizio di una lunga collaborazione che portò la Bourke-White a realizzare eccezionali reportage; durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale ebbe l’esclusiva per documentare il conflitto dal fronte russo.

La Bourke-White si sentiva investita di una missione: la fotografia poteva scuotere la coscienza dei lettori e cambiare le sorti del mondo. Grazie al coraggio e alla determinazione, fu la prima corrispondente di guerra della storia e aprì questa professione alle altre donne.

Livia Salvi

Didascalie foto:

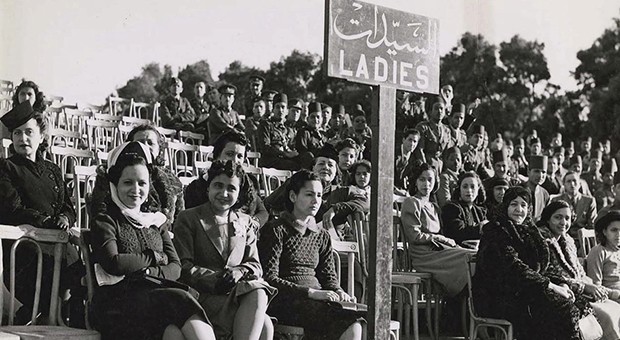

Foto 1 - Margaret Bourke-White

Foto 2 - Hats in the Garment District, New York City 1930, Margaret Bourke-White

Foto 3 - The Three Marys (Mary Hillier), 1864, Julia Margaret Cameron

Through women’s eyes

Julia Margaret Cameron, Margaret Bourke-White and the mark they left on the History of Photography

The invention of photography marked an era. Up until the beginning of the nineteenth century painting had been the only way of reproducing an image.

This new technique unsettled and divided public opinion: some believed it would replace drawing, others feared it, even considering it immoral, while others hailed it as the greatest invention of the century. Certainly, photography in the early days was very different from the photography we know today.

Daguerreotypes required very long exposure times and were heavy silver-plated copper plates on which the image appeared as a shadow. They were also known as “mirrors with a memory” and were unique pieces that couldn’t be reproduced. Many people were devoted to experimentation and research and within a few decades the technique was considerably improved.

Research was oriented towards achieving greater photosensitivity in order to reduce times, producing more than just one copy with good definition, and creating photographs suitable for printing on paper.

The development of techniques expanded the possibilities of the medium and, in the second half of the century, photographers began to explore new creative opportunities.

When Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) received her first photographic device as a gift from her daughter in 1863, her family hoped she would find new inspiration and interests after going through a difficult period, and this was precisely what happened.

Soon she was exploring all the different opportunities the device could offer and because she approached photography as an amateur, she was able to break away from the accepted standards of the era and develop a personal style.

Her portraits were deliberately out of focus, blurred, esoteric, and it was precisely this vagueness that filled them with charm and allure, exciting great interest particularly among the pre-Raphaelite painters; for the first time, there was talk of “the art of photography”.

Cameron had thus achieved her intention: in a diary of the period she wrote, “My first aspiration is to ennoble Photography and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art.” In 1865 she exhibited a series of photographs to the public at the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria & Albert Museum) in London and obtained permission to use some of the rooms in the museum as a photographic studio, qualifying her perhaps as the first “artist in residence”.

Margaret Bourke-White, the first war reporter

Research to improve photographic techniques continued ceaselessly, focussing on two main goals: reduce exposure times to a minimum, so that instant shots could be taken, and reduce the size of the equipment, making it portable.

In 1925 Leitz began selling a highly innovative product: Leica, a small device with a 35 mm film. This camera was incredibly successful and became the symbol of modern photojournalism, which was becoming better established during this period.

Newspapers began to publish photographs daily without this weighing heavily on publishing costs. In the thirties, periodicals created exclusively for the purpose of displaying photographs were published: the magazine “Life”, established in the United States in 1936, was the most famous.

The first cover of this magazine, which marked a turning point in the world of women’s photography, was in fact assigned to a woman: Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971). This was the beginning of a long collaboration that led Bourke-White to create exceptional news reports.

During World War II she provided exclusive coverage of the conflict on the Russian front. Bourke-White felt as if she had been entrusted with a mission: photography could shake up the conscience of readers and change the fate of the world. Thanks to her courage and determination, she was the first war correspondent in history and opened this profession up to other women.

Traduzione a cura di ViceVersaGroup